Why Is Your Pump Operating Off the Curve?

“Wishin’ and Hopin’”—both Dionne Warwick and Dusty Springfield had hit versions of this pop song in the early ’60s. The lyrical message is that you will not get want you want if you just sit around wishing and hoping; instead you need to take action to achieve the desired outcome.

The same advice holds true for pump performance. I witness an alarming number of people who unwittingly wish and hope their pump would perform in the proper manner, but they are wishing and hoping with total disregard of the system curve, pump capabilities, the laws of physics and the fluid properties. Time to take action.

I start my pump training courses with the simple personification that “pumps are stupid.” Put a centrifugal pump in any system, and it does not know where to operate. It is the system, not the pump, that dictates where the pump will operate on its performance curve—if the pump is even capable of operating at that point.

Further, and intended only as a comedic anecdote to help my students learn, I refer to the pump as the “husband” in this marriage with the system curve, aka the “wife.” Perhaps, and with ostensible apologies to the “PC Police,” I suggest that the marriage works best if the husband (pump) listens and obeys the wife (system). If there is a mismatch in the two, then divorce (pump and system failure) is imminent.

The pump will operate where its performance curve intersects the system curve, but we don’t always know where that point is—and just to complicate matters, it can change quickly because of many variables. Two roadblocks that make this determination difficult are:

- We frequently have no idea of the system curve geometry

- The pump is often forced off its published curve by outside factors

We will address the system curve calculation in a future article. For now, the system curve is the absolute summation of the system’s static head, pressure head, velocity head and friction head. The geometry of the system curve is directly related to the flow rate, pipe size, elevation changes and losses due to friction of all the components in the system. Note the system curve is dynamic and will change with tank elevation and system pressure changes. It will also change with valve position, system age, fouling and corrosion. This month’s article will address No. 2: How pumps can operate off their published curves, and we will look at a few common examples.

Causes for Operating Off Curve

Here are some of the common issues:

- worn clearances

- different or incorrect size impeller

- different or incorrect speed

- viscosity not corrected or accurate

- net positive suction head (NPSH) margin insufficient

- air entrainment and/or dual phase liquids beyond 3 percent

- inadequate submergence (also see air entrainment)

- partial or restricted blockage of the suction line

- operating the pump in the wrong direction

First Things First

To determine where your pump is really operating, you will need to calculate the pump performance curve in the field “as is.”

First, obtain a copy of your pump performance curve as published or purchased. Then, using the pump’s discharge valve position, create a series of several different flow rates (recommend at least six points including shutoff head), determine and record the suction and discharge pressures for each flow condition, convert these pressures to differential head and plot them on your curve. Be careful to correct for gauge elevations, temperatures and specific gravities.

Does your curve match the published curve? If it does within 5 to 10 percent, then there is likely no problem.

Let’s look at a few cases where the curve does not agree with the published curve. Each case tells a critical story to help understand what is happening with your pump and the system.

Worn Clearances

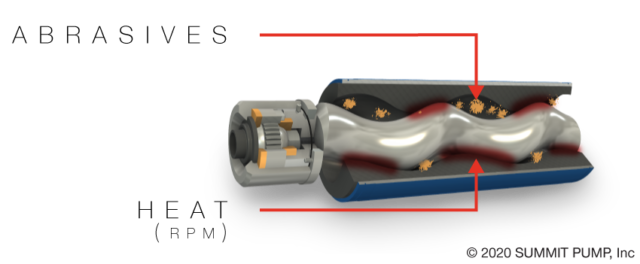

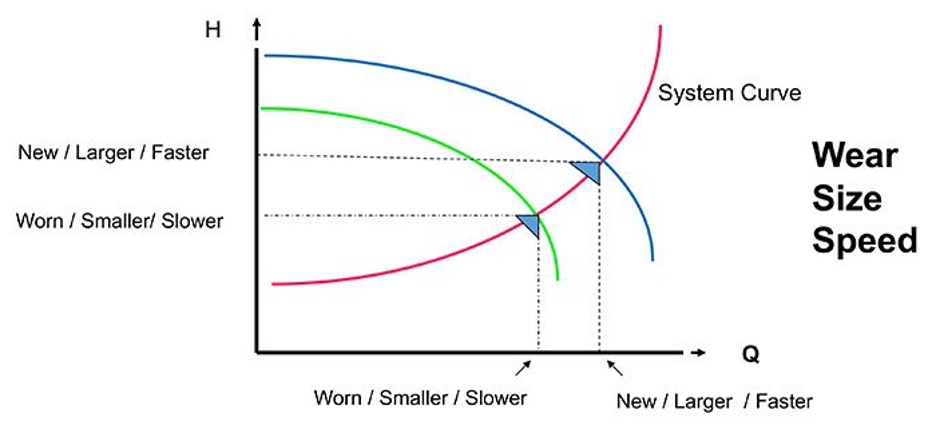

As a pump wears, the hydraulic performance deteriorates. Most people understand the pump efficiency will drop due to wear, causing the power to increase, but not all users realize that the head and flow will also deteriorate.

Note the revised pump curve still intersects the system curve, but the meeting point is at a lower flow rate and a lower head. See my Pumps & Systems articles from January 2016 and July 2017 for more details on this subject (Image 1).

Image 1. Effect on pump performance with wear, speed, impeller size (Images courtesy of author)

Image 1. Effect on pump performance with wear, speed, impeller size (Images courtesy of author)

It is important to understand if you are also plotting power on the curve: if the wear is simply the impeller or casing wear rings, the power will increase noticeably. But if the wear is in other areas such as internal passages, cutwater or the impeller vanes, the power will only increase a small amount.

A special note for ANSI pump designs that use the critical clearances between the impeller and the casing or stuffing box: the effect on power will be as the aforementioned pump with wear rings—that is, the power will increase noticeably.

Different Impeller Size or Speed

Often, one of the reasons for poor pump performance is that the wrong size impeller is in the pump. This could be caused by several different reasons, mostly human error. Another common reason is that the speed is different than perceived. This is common with systems that are controlled with variable frequency drives (VFDs) as part of the system control process. I mention both of these issues (speed and diameter) here because the performance manifests almost exactly the same as worn clearances.

See Image 1 to see the performance of smaller impellers or lower speeds.

Viscosity—the Kryptonite of Centrifugal Pumps

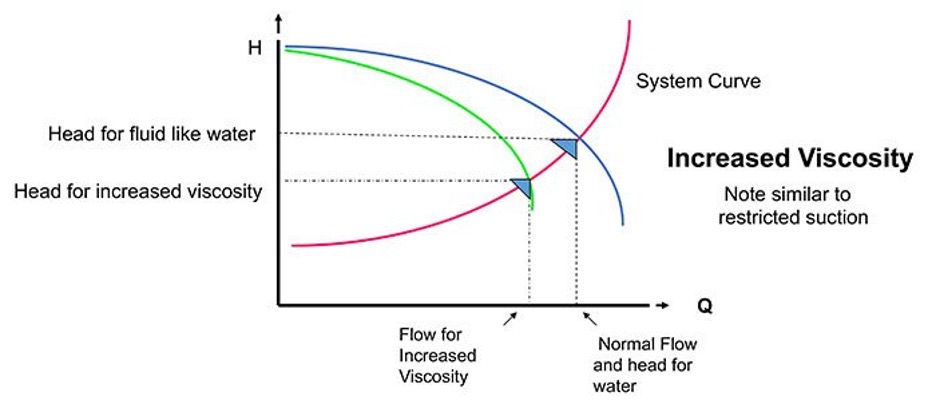

Viscosity has a direct and negative effect on centrifugal pump performance. The pump efficiency is affected the most, but head and flow are not far behind. Of course, all of these negative factors will contribute to increase the power required to pump the fluid at the same flow rate and head as if based on water performance.

Note that viscosity is directly proportional to temperature, so be cognizant of the fluid temperature. Also, smaller pumps are more affected by viscosity due to the smaller passage size.

See Image 2 for how viscosity will affect the pump performance, and also refer to my article on this subject from the November 2017 issue.

Image 2. Performance effect with increased viscosity

Image 2. Performance effect with increased viscosity

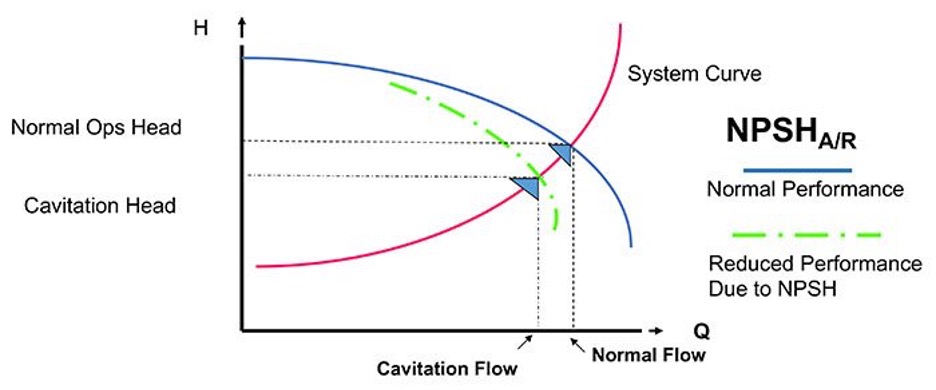

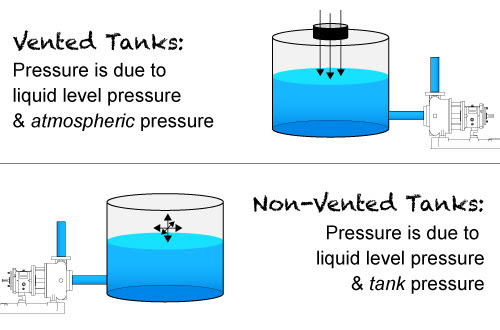

Insufficient NPSH Margin

Pumps require a certain amount of NPSH to operate satisfactorily at a given point of head and flow on the curve to prevent cavitation. The points are empirically determined by the manufacturer and are denoted as net positive suction head required (NPSHr).

The suction system itself must in return provide a certain amount of NPSH, and that is referred to as net positive suction head available (NPSHa). There must be more NPSHa than NPSHr for the pump to operate satisfactorily. The difference is referred to as the margin or ratio.

NPSHa ÷ NPSHr = margin ratio

NPSHa – NPSHr = margin

Equation 1

Refer to Hydraulic Institute 9.6.1-2017 for details.

A frequent field issue is that the margin calculations were not done, not done correctly or there were changes in the pump and/or system that have not been accounted for. A common issue in the field is that the pump has sufficient margin at lower flows, but as the flow rate increases the pump will begin to cavitate. See Image 3 to see how insufficient NPSH margins affects pump performance.

Image 3. Insufficient NPSH—pump will cavitate at higher flow rates (compare to Image 5 restricted flow)

Image 3. Insufficient NPSH—pump will cavitate at higher flow rates (compare to Image 5 restricted flow)

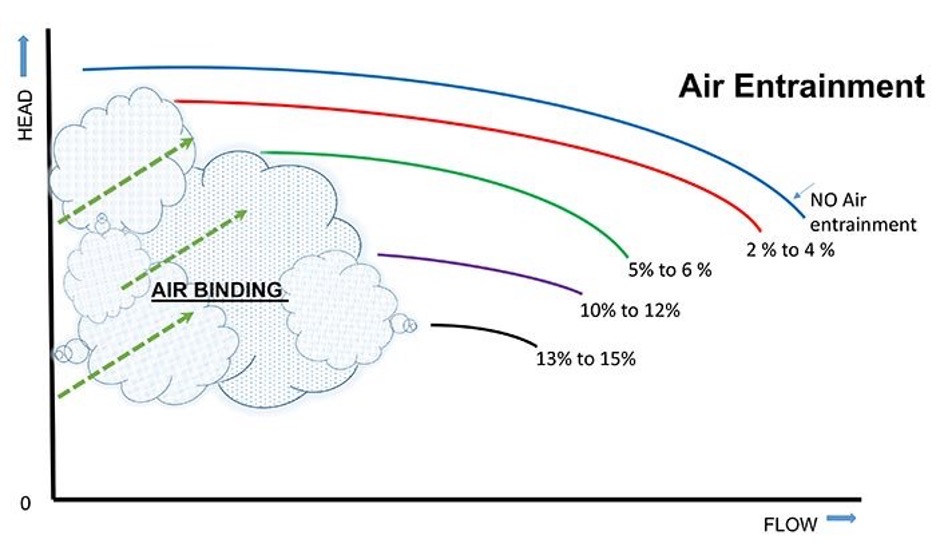

Inadequate Submergence & Air Entrainment

The pumped fluid could have air entrainment from different sources for many reasons, but a common cause is insufficient submergence.

No matter the source of the air, standard centrifugal pumps cannot handle it well. At about 3 to 4 percent air entrainment, the pump performance will drop off as if the impeller was trimmed to a smaller diameter or the pump is being operated at a lower speed.

Please refer to my April 2016 and December 2017 articles for details on air entrainment and pump performance.

Also note that at low flow rates the fluid velocity is insufficient to “sweep away” the air that collects in the impeller eye. Consequently, the pump will become blocked (air bound) and will stop pumping or it will surge in a destructive and alternating cycle of air blockage and subsequent flow passage.

See Image 4 to see how air entrainment de-rates the pump performance.

Image 4. Effect on pump performance with increased air entrainment

Image 4. Effect on pump performance with increased air entrainment

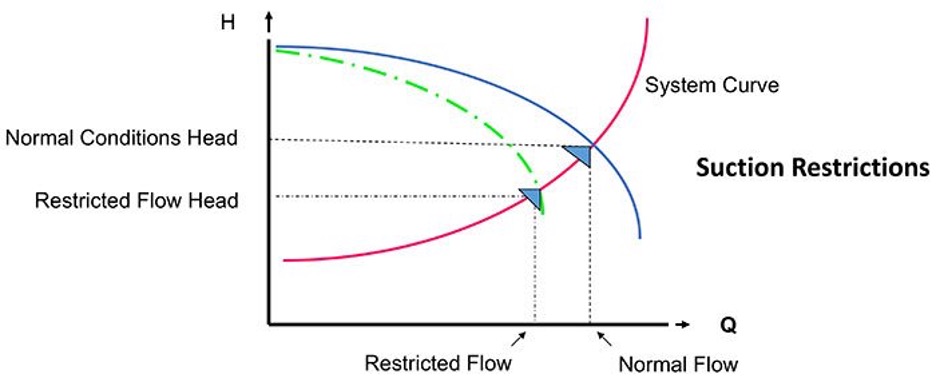

Restricted Pump Suction

This issue typically manifests on new construction, post repair startups and when there is equipment installed in the suction line like a filter press, foot valve or strainer. As flow increases the head will drop off. This is similar, but different, than an NPSH margin issue.

See Image 5 to see how a suction restriction affects the pump curve.

Image 5. (left to right). Effects of suction line restriction. Actual performance will vary with the magnitude of the restriction.

Image 5. (left to right). Effects of suction line restriction. Actual performance will vary with the magnitude of the restriction.

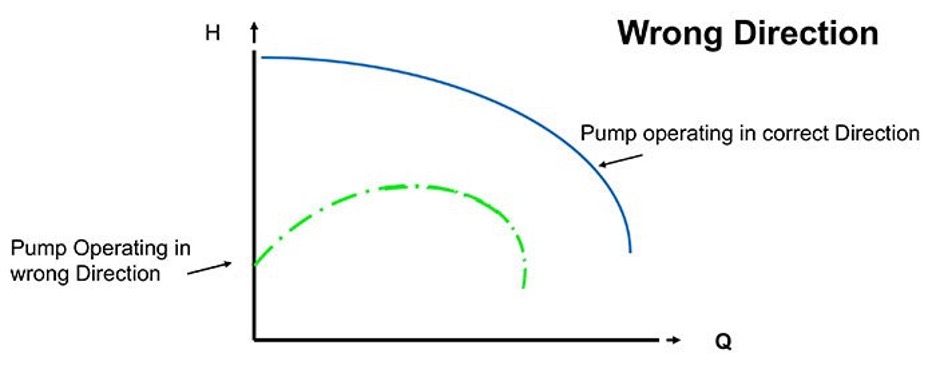

Wrong Direction

I have written about pumps operating in the wrong direction many times because it is unfortunately an all too common issue. In the case of ANSI pumps (with impellers that thread on the shaft), the pump will, 99 percent of the time, pronounce in a millisecond that the direction is incorrect as the impeller grinds into the casing creating expensive and extensive damage and yet hopefully tripping out the motor.

For pumps that have impellers keyed to the shaft it may or may not be obvious. Pumps running backwards will typically be a little noisier and exhibit higher vibrations than a similar pump operating in the correct direction. But this is not always easy to determine in an operating plant due to background noises and other field interference.

Performance will depend on the pump design and is mostly, but not always, a function of the impellers’ specific speed. As a general rule, the flow rate in a reverse operating pump will be about 50 percent, and the head will be somewhere near 60 percent. The higher the impeller specific speed, the lower the head will be. Concentric casing designs will yield different results.

Please see Image 6 to see how reverse rotation may affect pump performance.

Image 6. Effects of running the pump in the wrong direction. Assumes low- to mid-range specific speed. Do not confuse with pumps running as turbines.

Image 6. Effects of running the pump in the wrong direction. Assumes low- to mid-range specific speed. Do not confuse with pumps running as turbines.

Conclusion

Pumps will operate where the system curve dictates, but the pump curve is not always where you think it is and neither is the system curve. You will not get the performance you need and want by just wishing and hoping—you need to measure the parameters and manage the system.

-Jim Elsey

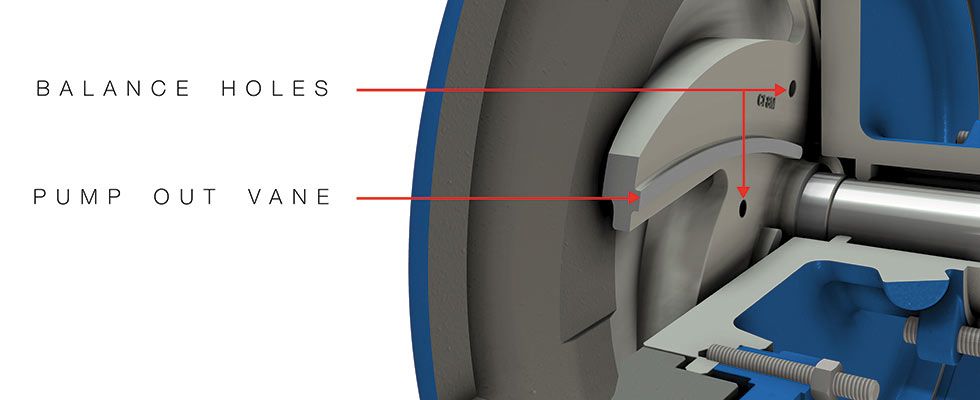

IMAGE 1: Radial or axial, the resultant forces are mostly due to the hydraulic pressure acting on the impeller. F=PA. Force is equal to the pressure (P) working on the effective surface area (A) presented by the impeller shroud(s). (Images courtesy of the author)

IMAGE 1: Radial or axial, the resultant forces are mostly due to the hydraulic pressure acting on the impeller. F=PA. Force is equal to the pressure (P) working on the effective surface area (A) presented by the impeller shroud(s). (Images courtesy of the author)